Peaks of the Icefields Parkway – Part 4

“A new world was spread at our feet; to the westward stretched a vast icefield probably never before seen by the human eye, and surrounded by entirely unknown, unnamed, and unclimbed peaks.”

J Norman Collie, 1898

It may be hard to imagine now, but the Columbia Icefield and surrounding peaks have only become accessible within the last century. When J Norman Collie and his climbing companion Hermann Woolley viewed the icefield from the summit of Mount Athabasca in 1898, it was like discovering a whole new world. The area was remote and difficult to reach. There were no roads and no railroads. Fur trade routes and First Nations trails were to the north and to the south. The icefield was in no-man’s land. It’s no wonder Collie believed he and Woolley were first to view the awe-inspiring icefields in 1898.

Since that time, the area has opened to adventurers and explorers and most peaks now have names. Some, in fact, have had several names. This list tells the stories behind the naming of some of the most significant peaks and geographical features along the Icefields Parkway.

Huge thanks to Dave Birrel of www.peakfinder.com for allowing us to borrow content from his amazing website. Please visit this website to find out everything you’d want to know about almost all the Mountains in the Rockies.

This is Part 4 in a series of 6 posts which all together will cover 60 of the most scenic and interesting mountain peaks that you’ll ride past during the tour. Enjoy!

1. Howse Pass / Peak and Saskatchewan River crossing (from The Crossing Resort Website)

Tonight we stay at The Crossing Resort, surrounded by Mountain Peaks. After getting settled in to your comfy rooms and having dinner you may find yourself sitting back wondering how these resorts came about and the history of Saskatchewan River Crossing.

Read on for a brief history of the area and resort. For a more detailed interview with the current owners of the property that we published earlier in the season, click here.

The Crossing has long been identified as a strategic location in the history of the Canadian West. At this location, the Mistaya and Howse Rivers meet the North Saskatchewan River. In the early 1800’s, this was the route of the Fur Trade and at this location, the Fur Traders crossed the North Saskatchewan River, following the Howse River to the Howse Pass which breeched the Rocky Mountains into what is now the province of British Columbia.

Howse Pass (1,539 m, 5,049 ft.) The pass is located in Banff National Park, between Mount Conway and Howse Peak. From here waters flow east via Conway Creek, Howse River, North Saskatchewan River to Lake Winnipeg and Hudson Bay. To the west it drains by the Blaeberry River to the Columbia River and on to the Pacific Ocean.

The pass was used by First Nations people including the Kootenay to the west and Piegan Blackfeet to the east. In 1806 two fur traders from the Hudson’s Bay “Rocky Mountain House” cut a rough road from the Howse River toward the pass. In June 1807 David Thompson crossed through the pass to the Columbia River and named it after Joseph Howse, a Hudson’s Bay Company factor who actually made the traverse in 1809. Howse Pass is lower than many other passes in the Rockies and it was considered for the Canadian Pacific’s rail line but the Kicking Horse Pass was chosen instead. The pass was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1978.

Howse Peak (3290m) which is located just to the south of Mt Chepren (mentioned shortly in a future blog post) is one of the highest Mountains in the area and is geographically significant because at it’s summit the continental divide makes a ninety degree turn and trends north east – southwest for twenty kms.

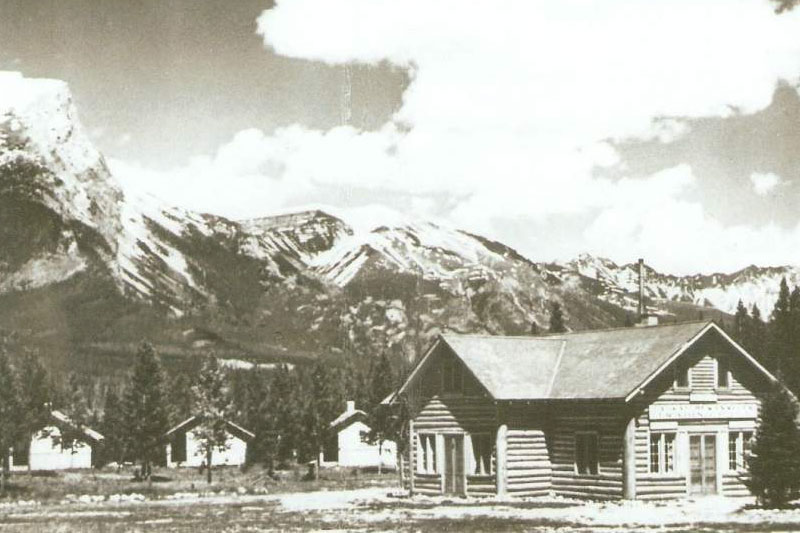

The Crossing Resort: The Crossing continues to be a key location to this day. In 1940, the first Banff-Jasper Highway was opened to the public and in 1948 George Brewster built the Saskatchewan River Bungalow Camp consisting of what are now the office and two cabins.

In 1963 the new Banff – Jasper highway (now The Icefields Parkway) was opened and The Crossing was relocated to its present site. Robert & Naomi Smead purchased the resort at this time. What we use today as the office was the main lodge at the original location and became staff accommodations when The Crossing was moved to its present location.

Then in 1968, Highway 11, The David Thompson Highway was completed, joining the Icefields Parkway at The Crossing, providing easy access to the Icefields Parkway for residents of Rocky Mountain House, Red Deer and Central Alberta.

In 1975, the resort was purchased by the Fikowski family. At this time the resort operated from May until September with only the cabins available for guest accommodation. It took a whopping 28 staff to operate the property that at that time offered 46 seats in the Dining Room and 64 seats in the Cafeteria. The Gift Shop was a cozy 600 square feet. A cabin at that time rented for $10.00 per day with one pail of water and $15.00 with two pails. An average day was one bus and the busiest day of the year was 7 buses.

Today, The Crossing Resort offers 66 deluxe rooms, a 250 seat Dining Room, 125 seat Cafeteria, 70 seat Pub and a 3000 square foot General Store and Gift Shop.

2. Mount Murchison 3333m (10936ft.)

As you relax on your deck after a hearty all you can eat buffet dinner at The Crossing Resort make sure you turn your gaze for a while to the massive lump of rock to the south of the resort called Mt Murchison. It’s a beauty and early season it’s upper slopes will be covered in snow.

Just after sunset watch for the mountain to briefly change to a dark red colour in an optical phenomenon called alpenglow. Alpenglow occurs when the sun is just below the horizon, and there is no direct path for the sunlight to reach the mountain. Instead the sunlight is reflected off airborne precipitation, ice crystals or particulates in the lower atmosphere. The red / orange colour is because the light of the nearly rising or recently setting sun is passing through more of the atmosphere than when it is high overhead. The atmosphere strips out the blues first and leaves us with warm, red/orange light.

You’ll notice that all the forest on the lower slopes of the mountain have been burnt all the way to the Icefields parkway. Back in July 2014 a wildfire was sparked by lightning in the area and a large controlled burn on the mountain was carried out by Parks Canada to contain the fire so that it would burn it’s self out. The mission was a success and you can see clearly where they stopped the controlled fire at a rocky creek drainage. We were at the resort on tour at the time and got some great photos of the event, see below.

The mountain was named by James Hector, scientist with the Palliser Expedition in 1858 for Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, a Scottish geologist.

Murchison was born to a wealthy Scottish landowner in 1792. After marrying he traveled in Italy for two years before returning to Scotland and selling his estate. He spent the next few years fox hunting, then discovered a passion for geology. His research led him to establish the Silurian System, a geologic unit used for classifying rocks formed in a defined period of earth’s history. His contribution impacted the coal industry by establishing a boundary below which coal would not be found, thereby saving mining companies much money through wasted exploration efforts.

He served as president of the Bristish Association for the Advancement of Science, was director general of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, and was president of the Royal Geographical Society for many years. Over his lifetime, he was awarded many honours by scientific societies. He was knighted in 1846 and made a baronet, a hereditary title given by the British Crown.

Murchison was president of the Royal Geographical Society when Palliser presented his plans for exploration of the southern prairies of British North America.

3. Mount Forbes, 3612m (11851ft.)

Although this huge mountain can be hard to see from The Crossing Resort (quite often shrouded in cloud and it’s height disguised by closer but lower peaks, I thought it would be worth a mention as it’s the highest mountain entirely within Banff National Park.

James Outram and Norman Collie‘s parties combined forces in 1902 to attempt Mount Forbes. Collie greatly admired the peak referring to, “awesome precipices soaring to a ramp of stainless snow whose knife-edged ridges culminate in a sharp pyramid that pierces the blue heavens like a javelin.”

There had been some competition and even animosity between the two as Outram had made the first ascent of Mount Columbia following Collie’s preparatory exploration of the area. The fine Victorian manners of both gentlemen were demonstrated on this challenging first ascent. At one point Collie, rather than increase the risk to his companions of being the fourth on the rope, abandoned the ascent. Outram feeling that Collie, “more than all the rest, deserved the gratification and honour of being the first to conquer Mount Forbes,” sent the two guides down to accompany Collie to rejoin the party. The two guides were Christian Kaufmann and Hans Kaufmann who Collie was to honour by suggesting the name Kaufmann Peaks for two nearby summits.

It is clear from letters written to Charles S. Thompson that Norman Collie regarded Mount Forbes as the most difficult of all his climbs in the Canadian Rockies. This was due to the fact that much loose, “rotten” rock was encountered and also because of a shortage of climbing rope available to the large party.

In 1926, J. Monroe Thorington wrote of Mount Forbes, “What is there left to say of Mt. Forbes -that wonderful mountain we had placed, with some temerity, at the end of our climbing programme? It is a height to which one may look up, as if Kim to the rim of the Himalaya, and say,’Surely the Gods live here.’ Skyward rearing,like a watch-tower of the immortals it is a perpetual challenge.”

It is not surprising that a peak as prominent as Mount Forbes was named by James Hector of the Palliser Expedition. Edward Forbes was Hector’s Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh.

Edward Forbes (1815-1854) was a pioneer in the field of biogeography and palaeontology. As a student at the University of Edinburgh, he studied medicine, but also undertook instruction in natural history.

In 1833 Forbes undertook a botanical tour of Norway. He then gave up medicine as a career and attended natural history lectures in Paris before travelling to Algeria to study fresh-water and land molluscs. He served as naturalist on HMS Beacon, surveying both the Grecian Archipelago and parts of Asia Minor in both 1838 and 1841.

In 1842, Forbes became the secretary and curator of the Museum of Economic Geology, run by the Geological Society of London. In 1843 he was appointed professor of botany at King’s College, London. In 1844 he resigned from the Museum of Economic Geology to take up the duties of palaeontologist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain. In 1851 he progressed to professor of natural history at the Government School of Mines. 3 years later he was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Edinburgh, but died 6 months after taking up the position.

4. Mistaya River Valley and Mistaya Canyon

We’re on day 3 of the tour now and you’ll turn left out of the hotel parking lot onto the Icefields Parkway, go briefly downhill, Across the bridge over the North Saskatchewan River where you’ll be treated with the first big bump of the day. 3km into the climb you’ll see a parking lot to your right with signs to Mistaya Canyon. A 500-metre (0.3-mile) trail drops down to the Canyon—one of the more impressive limestone slot canyons in the mountain parks. A bridge spans this narrow gorge, providing a good perspective of how the rushing waters of the Mistaya River have cut deeply into limestone bedrock to form this deep sheer-walled canyon. From this vantage point, you can also see how the action of water has sculpted the canyon, dissolving the limestone to widen the gorge and, with the help of rocks and gravel carried in the powerful current, eroding rounded pothole depressions into the walls.

In the early 1800s, fur traders referred to this river simply as the South Fork of the Saskatchewan River. When the first pack-trains passed this way at the turn of the 20th century, it was called Bear Creek. Later, the name was changed to Mistaya, the Cree word for grizzly bear.

5. Kaufmann peaks 3094m (10150ft.) north summit, 3109m (10201ft.) south summit.

As you approach the top of the first climb of the day on day 3 of the tour you’ll see some spectacular mountains ahead of you and to your right.

Kaufmann Peaks are a striking pair of very similar mountains which share a lovely glacier below them. Their summits are almost identical in outline, within fifteen metres of being the same height, and both appear to be split near the top creating twin summits. On the right hand summit, this effect is caused by a patch of snow near the peak. Quite appropriately they are named for two brothers. Christian and Hans Kaufmann were members of a well established Swiss guiding family and worked as guides for the CPR.

Both were highly respected and were in constant demand because of their mountaineering skills and to some extent because they both spoke excellent English. Their nephew, Peter, guided parties in 1930.

Prior to coming to Canada, Christian Kaufmann guided in the Alps, his most famous client being Winston Churchill who he led up the Wetterhorn in 1894. Christian first came to the Canadian Rockies in 1900 with Norman Collie and his party on their expedition to the Bush River. He returned again in 1901 as one of four guides contracted to Edward Whymper. Completing 36 first ascents in the Canadian Rockies, he made fifteen of those in 1901 and ten more in 1902 when he again climbed with Norman Collie.

Hans Kaufmann completed twelve first ascents in the Rockies during the years 1901 to 1904.

6. Epaulette Mountain 3095m (10155ft.)

We’ll be waiting to cheer you on at the top of the first climb of the day. Feel free to take a quick breather here and check out the surrounding Peaks including this beauty. Named in 1961. The glacier which seems to hang on a narrow shelf above the steep cliffs which drop into the valley, was thought to resemble to the shoulder ornament which is part of some military uniforms generally worn by fairly high ranking individuals.

7. Mount Chephren / Waterfowl Lake 3266m (10716ft.)

This one’s one of my favourite mountains on the tour. Even before arriving at the Crossing Resort near the end of Day 2 of the tour you can see the summit of this monster on the horizon. During dinner at The Crossing Resort you’ll have a great view of Mt Chephren and at the top of the first climb of the day it will reappear in more detail getting larger and more impressive as you ride. We’ll regroup and have a snack stop on the shores of Waterfowl Lake, at the base of the mountain. The steep cliffs of Mount Chephren are most impressive as they rise 1600 metres above the valley floor. The lower part of the mountain is made of reddish and pinkish quartzites of Lower Cambrian age. The higher levels are made of younger, grey limestones.

Mount Chephren was named Pyramid Mountain by J. Norman Collie in 1897. At the same time he named its neighbour, which was covered in snow, White Pyramid. Pyramid Mountain, in contrast, had very little snow.

The peak was a favourite of Mabel Williams who, in 1948, wrote a wonderful guidebook for what was then called, “The Banff-Jasper Highway.” Of Mount Chephren she wrote, “Even in this region of magnificent peaks, Mount Chephren stands out with a supreme majesty and beauty all its own. Among all mountain lovers it will always hold high place. Its dark frontal tower of purplish rock rounded to a beehive, its immense, deeply carved buttresses, the symmetrical bands of darker rock and dazzling snow which crown its summit give it an individuality which stamps itself at once on the memory. A luxuriant forest throws its cloak of living green about its feet, but, above, the great walls rise in naked precipices for nearly a mile. Lying upon the main mass of the mountain is an immensely thick ice cap which sweeps down around the great tower in a pure white snow saddle like a white scarf flung over its shoulders.”

In 1918 the Interprovincial Boundary Commission decided that Pyramid Mountain’s name must be changed in order to avoid confusion with the Pyramid Mountain near Jasper. J. M. Thorington, a prominent mountaineer and author of the era, liked the association of the peak with the pyramids of Egypt and recommended the name Chephren. Chephren, or Khafre, was the fourth pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt and built the second of the three Great Pyramids. His reign began in 2565 BC and it is his likeness which is thought to have been the model for the Sphinx. White Pyramid‘s name was thought to be different enough from the Pyramid Mountain near Jasper and that name was retained.

8. Mt Patterson / Snowbird Glacier, 3197m (10489ft.)

After refuelling at the Waterfowl Lakes rest stop you’ll have just 10 kms of relatively easy riding before the big bump (Bow Pass) Just before the big bump starts you’ll see us parked on the right hand side. You’ll likely be going fast as there is a short downhill before the big bump, but don’t forget to look to your right and maybe even pause for a bit to take in Mt Patterson and Snowbird Glacier.

The massive Mount Patterson covers a large area and towers almost 1500 metres above the Icefields Parkway below the northern slopes of Bow Pass. The mountain rises in three levels, with glaciers hanging picturesquely between them. Between the main portion of the peak and a high outlier to the northwest, we see a smoothly contoured line of moraine which was left following the last advance of the Snowbird Glacier which adorns a very large cirque on the north east side of the mountain. One of the most attractive glaciers in the Rockies, it drapes over the cliff bands with wings spread.

On calm days in the summer, the roar of the waterfalls and meltwater streams in the cirque is constant.

This is one glacier whose appearance has probably changed very little over the past century. The extent of the snowbird’s wings are limited by the width of the ledges upon which they rest so any additional build up of ice simply falls over the cliffs to the snowbird’s tail below.

John Duncan Patterson was a founding member of the Alpine Club of Canada. He became its third president in 1914 and served until 1920. Born in Richmond Hill, Ontario, Patterson made his living as a farmer. Although he enjoyed climbing, he spent much of his time leading less energetic members of the Alpine Club. According to Arthur O. Wheeler, “He was one of Nature”s gentlemen whose kind and unselfish character placed him high among his fellows, he will be remembered as one who was most worthy.”

9. Caldron Peak 2911m (9550ft.) / Peyto Lake / Mt Peyto

After conquering the big bump (Bow Pass) if it’s a nice day and the weather in co-operating you’ll be stoked to find out that there is an optionally mandatory bonus round in store for you for an extra chocolate pretzel. You’ll have to trust me, you’ll thank me later.

The one km bonus round takes us further uphill to the Peyto Lake view point and if it’s looking busy we’ll likely go for a quick 7 min hike to a much quieter view point where we’ll have lunch.

It’s a spectacular Glacial fed lake with unbelievable colours that you have to see yourself to believe. The colours are caused by significant amounts of glacial rock flour flowing into the lake from Peyto Glacier, and these suspended rock particles give the lake a bright, turquoise colour.

The back drop of Caldron Peak (named simply because of Caldron Lake nearby) towering over the lake adds to the spectacle and to finish it all off, you can see almost 40km down the valley that we’ve been riding up during the day. From here you can see the summit Glaciers of Mt Wilson (the mountain that sits behind The Crossing Resort where we stayed last night). To your left you’ll catch a glimpse of the Peyto Glacier that used to reach down as far as the lake back in 1885 and above that. Peyto Lake drains into Mistaya River which flows through Mistaya canyon that was covered in a previous post.

To the left of Caldron Peak you’ll see Mt Peyto (2970m) and behind you Mt Jimmy Simpson (both covered in the next blog posts)

Bill Peyto was born in England in 1869 and traveled to Canada in 1887, where he worked as a labourer on the railway. He built a log cabin on the Bow River offered guiding services to visitors. He was employed as a park warden in Banff National Park for 23 years. He earned the respect of climbers such as Walter Wilcox, J Norman Collie and others, for his guiding and climbing abilities in rough and dangerous terrain.

Peyto was involved in the Boer War as a horseman and in WW I, where he was injured. He returned to the solitude of the Rockies each time. Between the two wars, he married, but his wife died and left Peyto with a young son, whom he sent to live with his wife’s family soon after her death.

It is said that often when he was traveling with a party, he would leave the group at Bow Summit campground and slip away to spend the night alone at Peyto Lake.

10. Peyto Peak 2970m (9745ft.)

Named by Walter D. Wilcox in 1896. Peyto, Ebenezer William “Bill” (Bill Peyto was an early outfitter in the Banff and Lake Louise areas.)

The summer of 1934 during which Conrad Kain led the first ascent of Peyto Peak was Conrad’s last in the Rockies. In his autobiography, “Where the Clouds can Go,” it is written that Conrad took the “summit stone” from the mountain and delivered it to his old friend Bill Peyto in Banff.

After arriving in Canada from England in 1886, Peyto worked for the CPR, homesteaded, and prospected before entering the outfitting business with Tom Wilson. When he was chosen to lead Whymper to Vemilion Pass he had acquired a solid reputation for his work withWalter Wilcox, Norman Collie, and others.

Norman Collie wrote of Bill Peyto, “Bill is very quiet in civilization, but becomes more communicative around an evening campfire, when he delights to tell his adventures. His life has been a roving life. The story of his battle with the world, his escapades and sufferings of hunger and exposure not to mention the dreams and ambitions of a keen imagination with their consequent disappointments, has served to entertain many an evening hour. Peyto assumes a wild and picturesque though somewhat tattered attire. A sombrero, with a rakish tilt to one side, a blue shirt set off by a white kerchief (which may have served civilization for napkin), and a buckskin coat with a fringe border, add to his cowboy appearance. A heavy belt containing a row of cartridges, hunting-knife, and six-shooter as well as the restless activity of his wicked blue eyes, give him an air of bravado. He usually wears two pairs of trousers, one over the other, the outer pair about six months older. This was shown by their dilapidated and faded state, hanging, after a week of rough work in burnt timer, in a tattered fringe knee-high. Every once in a while Peyto would give one or two nervous yanks at the fringe and tear off the longer pieces, so that his outer trousers disappeared day by day from below upwards. Part of this was affection, to impress the tender foot, or the “dude,” as he calls everyone who wears a collar. But in spite of this Peyto is one of the most conscientious and experience men with horses that I have ever known.”

Bill and Edward Whymper seemed to get along reasonably well during their initial trip together and although he found numerous faults with his Swiss guides, he felt that Peyto had, “properly executed his commission.” Later in the summer however, after a severe tongue-lashing from Whymper for coming back to camp to early from trail clearing work in the Yoho Valley, Bill walked out on him with the excuse that he had to take two sick horses back to Field.